It’s a common trope among certain types of financial planners: “Save more, spend less… and don’t do anything stupid.” So celebrated is the phrase with some advisers, organizers of a recent conference emblazoned it across baseball caps – attendees proudly wearing the hats as if they were at a MAGA rally.

Beyond the condescending tone and hyperbole however, lies a particular kind of Wall Street fear mongering: Americans of all stripes are facing a looming retirement crisis to which there is no alternative. Cut out your lattes and other discretionary spending or you are destined for destitute. But don’t worry, we’re here to help – just buy our stocks, bonds and annuities.

There’s little doubt that in the aggregate, American’s need to save more. A Boston College survey reports that American’s face a $7.7 trillion retirement income deficit[i] – the difference between what we now have saved, and what we should have saved by now.

But unless you consider debt and taxes to be spending, saving more doesn’t require you to spend less.

Together, we Americans owe almost $14 trillion in combined household debt[ii] and pay over $2 trillion each year in state and federal income taxes.[iii]

If only there were a way to turn Debt & Taxes into Savings & Investment.™

Transforming debt and/or taxes into savings opens the possibility to keep our lattes. And what’s more, save adequately for retirement while spending more, rather than less on the many other things we care about.

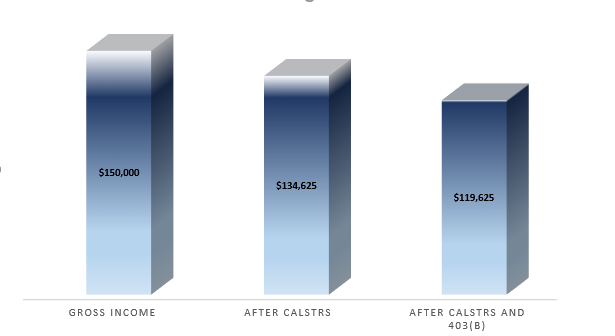

That’s because the very act of savings means not spending that same income. Consider for the moment a married couple, California educators earning a combined $150,000 a year. At first glance it might appear that this couple will eventually need to replace their $150,000/year earnings. Yet further investigation reveals that as California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) members, their gross paychecks are already reduced by 10.25% – the employee’s contribution to the retirement system.

That means our couple lives not off $150,000 of gross income, but less than $135,000 – as more than $15,000 a year is “saved” towards retirement.

And watch what happens to their retirement income needs if our CalSTRS couple starts saving 10% of their income via pre-tax 403(b) contributions:

This simple accounting exercise paints the picture Wall Street doesn’t want you to see, for:

The more you save, the less you need to save for.

And it’s not just $30,375 (the difference between $150,000 and $119,625 in our example) that doesn’t need to be saved for, it’s that difference adjusted for future inflation. Meaning that if inflation runs just 3% over the next 15 years, today’s $30,375 difference is tomorrow’s $45,945 that doesn’t need to be saved for.

Not having to replace $45,000 is like not having to have $1M saved for retirement – because a million dollars is roughly the amount it takes to generate $45,000 a year of sustained retirement income.

Of course if the more your save, the less you need to save for – it follows that the less you need to save for, the more you can spend.

But wait. Hold on a minute. Doesn’t that mean the more you save, the more you can spend?

Yes! Indeed it does!

What initial appears to be a paradox, is actually a fundamental accounting truth:

· The more you save, the less you need to save for.

· The less you need to save, the more you can spend.

This leads to the paradox:

· The more you save, the more you can spend.

But this only looks like a paradox because we tend to think of savings as coming from (i.e. “out of”) spending. But when savings & investment come not at the expense of spending, but at the expense of debt and taxes – existing spending is spared and the paradox disappears.

And along with it any fear and loathing associated with “save more, spend less… and don’t do anything stupid.”

Turning Debt & Taxes into Savings & Investment allows you to Save More, Have More and Spend More.™

Often, more than you ever thought possible.

[i] Center for Retirement Research at Boston College

[ii] Federal Reserve Bank of New York

[iii] FRED Economic Data, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; www.usgovernmentrevenue.com